A Brief (and Fascinating) History of Breastfeeding and its Alternatives

Breastfeeding has never been without cultural commentary. Breast milk is arguably one of the most provocative of bodily fluids—we do not feel as passionate about urine, sweat, snot, or tears—and yet breast milk is a biggie. Since the beginning of time, breast milk has been revered…and has been a substance of great contention. The history of breastfeeding is fascinating, especially seen in the context of our current culture about breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding has never been without cultural commentary. Breast milk is arguably one of the most provocative of bodily fluids—we do not feel as passionate about urine, sweat, snot, or tears—and yet breast milk is a biggie. Since the beginning of time, breast milk has been revered…and has been a substance of great contention. The history of breastfeeding is fascinating, especially seen in the context of our current culture about breastfeeding.

Breastmilk has been revered since ancient times. In Classic Greece, the milk of a Greek goddess was thought to confer immortality to those who drank it. It was Hera’s breastmilk that made Hercules invincible. It was Hera’s breastmilk that formed the Milky Way itself (so the story goes). The Mother Mary was exempt from sex, pain in childbirth, and perhaps many bodily functions (at least as the story goes)—and yet she breastfed. Baby Jesus at the breast of Mary has been one of the most popular and powerful artistic images for millennia.

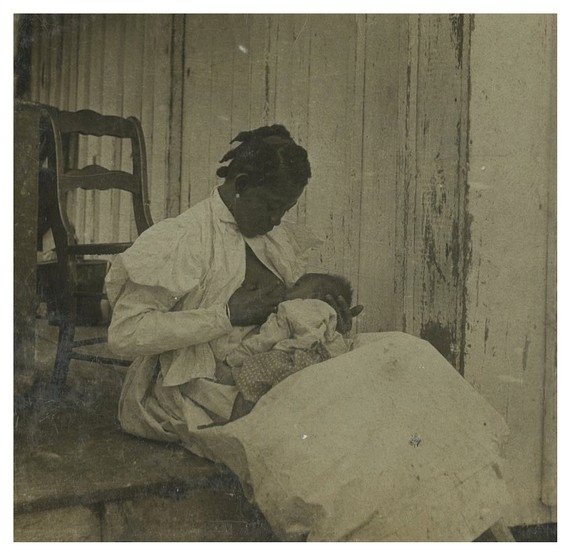

In ancient Egypt, wet nurses were exalted, despite their station as servants. They were invited to royal events. The children of royal wet nurses were considered kin to the king. In the great tale of Odysseus, only two individuals recognized the protagonist after his long absence from home—his loyal dog and his wet nurse. History has long recognized and exalted the special nature of the breastfeeding relationship.

But history has also complicated the breastfeeding relationship by adding cultural and ethical baggage to what is a biological function. We all know the current conditions around which our babies are fed—the importance given to breast milk, the push for formula by some and the rejection of it by others, the judgments that are made about women who want or don’t want to breast feed, women who can and cannot breastfeed, women who love and women who loathe breastfeeding, women who breastfeed a short while and those who nurse for years. It all comes highly charged.

And this high charge is nothing new. Formula vs breastmilk may be the contemporary dichotomy of choice (with a long list of subtler but equally divisive nursing nuances), but there have long been alternatives to a baby nursing at his or her mother’s breast.

We think of formula as a relatively new invention, but seeking breastmilk substitutes has long been a human enterprise (however unsuccessful many of those attempts). Breast-shaped clay bottles have been found in ancient sites in Europe that date back to 3500BC. Some historians believe that cows and goats were actually domesticated for the reason of providing a human breast milk substitute to infants. Babies may have suckled directly from these animals or been given human-fashioned devices very roughly akin to our modern baby bottles. Cow and goat milk substitutes largely fell out of favor when people learned that babies do not thrive on these human milk alternatives. Records from 18th century Europe, for example, show that babies given milk from these animals early on suffered greater rates of diarrhea and death compared to those fed human breast milk.

In addition to the long search for human milk substitutes, history shows us a long storied use of proxy milk givers—the practice of a woman other than the child’s mother nursing the child. This practice—called wet-nursing—is ancient and was one of the few ancient professions open exclusively to women. While not a common or accepted practice in the West today, wet nurses were once so popular that they had to advertise their services and compete for business. In 16th century England, how-to books were published for new parents about how to hire a wet nurse and what attributes she should possess. In Renaissance Florence, wet nurses gathered in public squares to sing songs in promotion and celebration of their services.

The use of wet nurses began in the upper classes; but, like many elite trends, it trickled down to the masses. (Formula use followed a similar trend.) By the 1600s in Europe, over half of all women were sending their babies off to be nursed by other women paid for such a service. In 1780, less than 10 percent of all Paris-born babes were nursed by their mothers, according to one historian. Expensive wet nurses even sent their babies off to be nursed by cheaper wet nurses so they could keep their supply for paying customers.

Why such popularity in wet nurses? Historians postulate many reasons for the rave. Some argue that men did not wish for their wives to breast feed for a gamut of reasons. One, it “ruined their maidenly bosoms.” Two, it took women and their affections away from men. Three, nursing was understood to compromise a woman’s fertility—the more a woman lactated the fewer babies she made. Men seeking progeny and heirs became great critics of lactating wives. There were also superstitions that intercourse somehow tainted breastmilk, another reason for a lack of support for breastfeeding.

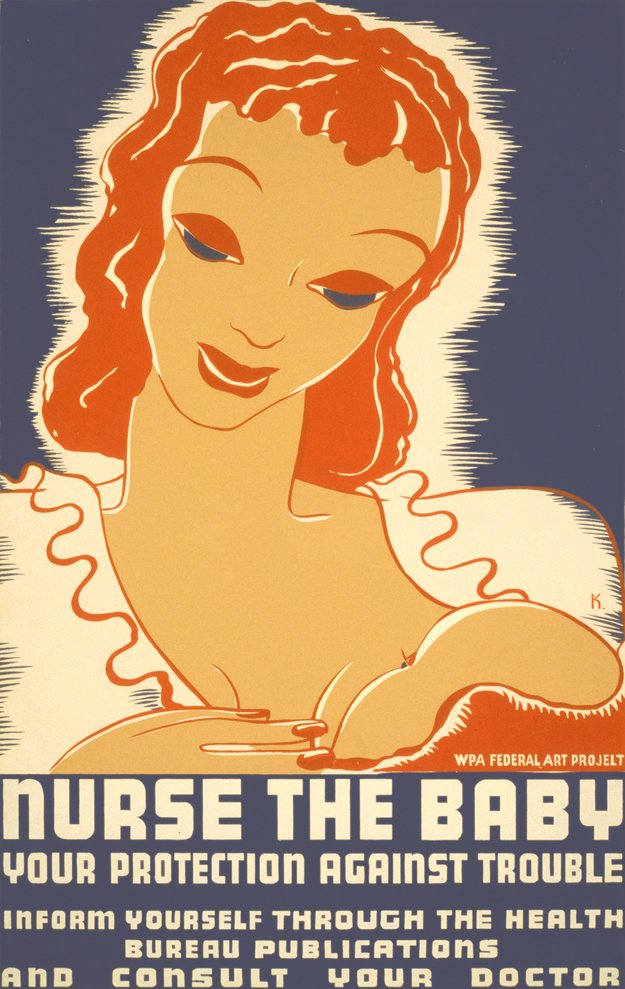

As with so many popular trends, there came a backlash against the use of wet nurses. Come the late 1700s/early 1800s—as part of the reform movements that swept across the social landscape of Europe and the United States—many women and men were calling for a return to in-home breastfeeding of babies by their own mothers. It was even billed as a feminist issue, though women still bore the brunt of this new creed—where once you were not a “good enough woman” if you DID breastfeed; now, you were not “good enough” if you DIDN’T nurse your babes. (Sound familiar?)

In 1793, the French declared that women who did not breastfeed were ineligible for welfare. In 1794, the Germans took it a step further and made it a legal requirement that all healthy women breastfeed their babes. By the early 1800s, elite women were bragging about their commitment to breastfeeding. Ah how the tides do change.

Though wet nursing has never regained popularity, similar themes have risen and met their demise in times since. The 20th century equivalent came with the advent of infant formula. Elite men and women again led the charge. Formula has historically been both hailed and rejected. At one time, formula was considered superior to breast milk in purity and nutrition. Later it was condemned as a harmful substitute for human milk. Other arguments swirl around these, many of which we know well for we still swim in these cultural waters.

The sway between breastfeeding and formula use has been striking in the United States in the last hundred years or so. Prior to 1930, most all mothers nursed their babies. By the early 1970s, only 22 percent of mamas breastfed, and most only for the first few weeks of life. Today, breastfeeding rates are on the rise. In 2011, 79 percent of newborn infants were breastfeed. Though the World Health Organization currently recommends babies breastfeed for 2 years, many nursing pairs do not breastfeed that long. Of infants born in 2011, 49 percent were breastfeeding at 6 months and 27 percent at 12 months.

Women throughout all of history have been subject to the cultural ideals and mores of the current day. All women throughout time have done their best, given the constraints of work, responsibility, familial and social expectations, desire, health, and ability.

Please note that this article does not attempt to be exhaustive in covering of breastfeeding's history, which is certainly a topic that could be covered in MUCH greater detail. This article does not cover historic breastfeeding trends worldwide, but rather, primarily focuses on Western culture, and even within this sphere of focus, much is surely uncovered. We invite you to delve further into this rich history should you so desire and share with us your interesting findings!

The information in this article is largely based on a chapter from Natalie Angier’s phenomenal book “Woman: An Intimate Geography.” For all those who love and care for the female body, this book is an incredibly insightful and valuable read.